PhD Students

I like PhD students, and I think they mostly like me (although they have been known to give me a bollocking from time to time). I have been primary supervisor for Paula Rowe, Marta Narkiewicz, Carmen Kohl, Aviad Hadar and Stergios Makris (who successfully defended their theses in 2018, 2018, 2017, 2012 and 2012 respectively).

Stergios was looking at the Gibsonian notion of "affordances" (the automatic activation of motor plans during object perception), a topic that was followed up by Paula, with a view to applying it in a rehab setting. Stergios worked as a post-doc at the Universita degli Studi di Udine after his PhD, and then accepted a lectureship in the psychology department at Edge Hill University (link) while Paula helped me out as a post-doc RA and is currently an honorary researcher at City.

Aviad was interested in motor activation in situations of response conflict, particularly deception, and went back to Israel afterwards to (somewhat masochistically) train for a medical degree. However, he has kept his experimental hand in as a part-time post-doc (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev; link) and an honorary researcher at City. Some of his work prompted the grant application that funded Carmen's studentship. Carmen looked at models of speeded choice with TMS and EEG measures. After her PhD and a brief post-doctoral job with me, she moved on to further post-doctoral roles at Hong Kong Polytechnic University and Brown University, before shifting track to become a data scientist in the private sector.

Last but by no means least, Marta looked at various aspects of temporal perception, focussing on the question of whether we have a single internal clock a bit like a stopwatch. Rather than begging for research cash, she opted to help dole it out, moving on to work as a research grants officer at the Brain Tumour Charity.

Areas of interest

Consider an exploding truck (well, why not?) Different sensory features (e.g. the truck’s colour, the motion of its various bits, and the sound of the explosion) are analysed in separate areas of the brain, which become activated at slightly different times. This seems at odds with our experience of a unitary sequence of events in time. To support temporal perception, the brain must compute both when the truck exploded (an instant) and how long the truck was stalled (an interval). Instants and intervals form a seamless and coherent perception of ongoing time, but the neural and computational basis of these perceptual experiences is not yet clear. I have studied how information from different modalities is combined when we decide about the timing of events (like exactly when the truck exploded) or the duration of a stimulus, and have also investigated various aspects of our multisensory temporal experience, including the way temporal perception can adapt to recent sensory and motor experiences. Much of this work has been, or is being, carried out in collaboration with Derek Arnold (University of Queensland, Brisbane); I was a partner investigator on his ARC discovery grants on 1) distorted time perception, and 2) why time seems to drag or fly. Most recently, I have been awarded ESRC funding for a three-year project attempting to marry predictions from psychophysical models of relative timing with EEG measures of neural latency noise (with Derek as external co-investigator, and Elliot Freeman from City St George's as internal CI). The hard work on this grant is being carried out by our post-doc RA, Dan Hu. I have also collaborated on time-related projects with Warrick Roseboom (University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton), and co-authored reviews with Sukh Obhi (McMaster University, Hamilton) and Hugo Merchant (UNAM, Querétaro)

Imagine yourself driving your car one evening. As you turn a bend, a cat appears in your headlights. Should you brake hard, or perhaps swerve left or right? Successful speeded decision making of this kind has been fundamental to our survival as a species, and continues to pervade everyday life, but how do we really make these choices? Within psychology, the computational principle of continuous evidence accumulation has become the dominant account underlying models of speeded decision making. The key idea is that an internal decision variable builds up at a rate reflecting the strength of evidence for each alternative, triggering action when a threshold value is reached. Building on previous work from my lab (see below) and in collaboration with Tina Forster (at City) and Sven Bestmann (at UCL) I was PI on a Leverhulme-funded project aiming to test different models of rapid choice using both behavioural and neurometric (TMS and EEG) measures. The models we considered share the assumption of sensory evidence accumulation over time, but differ in many important details, such as the existence of one versus several decision accumulators, the stochastic versus deterministic nature of information accrual, and the presence of leakage and/or mutual inhibition in the decision process. The hard work was done by our post-doc Laure Spieser and our PhD student, then post doc, Carmen Kohl.

How is it that experts are able to quickly and accurately discriminate sporting scenarios as they unfold? To answer this question, researchers have presented first-person video of specific scenarios (e.g. cricket bowling, from the batsman’s perspective) and asked athletes to categorise the outcome (e.g. in-swinging versus out-swinging deliveries). The video is either truncated at various points in time (temporal occlusion), e.g. before the cricket ball is released, or modified to remove specific pieces of visual information (spatial occlusion), such as the movement of the bowler’s arm. Experts, unlike novices, are able to respond at above-chance levels based on specific early visual cues. In collaboration with Josh Solomon (another researcher at City) I was awarded BBSRC funds to assess this expertise by introducing classification-image approaches. In the variant we used, the video is greyed out, but permits observers to see some regions through translucent windows (“Bubbles”) at multiple random locations in space and time. The logic is that good performance will only be possible on trials where a bubble happens, by chance, to reveal a region that carries important information (e.g. the bowling hand prior to ball release). Hence the signal components that are guiding discrimination (e.g. informing the choice of a cricket stroke) can be discerned. This work was taken forward by our post-doc, Sepehr Jalali (subsequently a post-doc over at UCL before moving to the private sector) who was helped out by our post-grad RA, Sian Martin. If this technique appeals, we have published a methods-focussed paper describing our fun with bubbles - our code is here.

Where and how do sensorimotor decisions get made? Cognitive psychology started out by viewing the mind like a program running on a digital computer, with mental operations (like perceiving, deciding, and acting) happening one after another in series. However, the brain is a parallel processor, not a serial device. This raises questions about the potential for parallel motor planning, and the role of multiple brain regions in representing sensorimotor decisions as they evolve over time. My group have looked at the way perceptual and decision processes seem to leak into the motor system, such that plans for action exist even when we have no conscious intention to act. In our experiments, we often assess motor plans by stimulating the motor cortex to evoke specific muscular responses that are tied to action preparation. These responses index plans for action, and can even reveal response tendencies we would like to keep hidden, such as when we veto an automatic response in order to lie. This work was previously taken forward by my PhD students Stergios Makris and Aviad Hadar, and followed up by Paula Rowe.

The chronostasis illusion was the major focus of my PhD and post-doctoral research. The term chronostasis describes an overestimation of the duration of a stimulus perceived following a movement. For example, in saccadic chronostasis, an object fixated following a saccade (a very rapid eye movement) is typically judged to have been seen for longer than is actually the case. This effect is most commonly experienced as the stopped clock illusion (the momentary impression that a clock has stopped when we first glance at it). The illusion is an interesting example of the way in which the brain constructs a coherent conscious visual experience when the temporal sequencing of events is made ambiguous by movement. Much of this work was completed in collaboration with John Rothwell (ION, UCL) and Patrick Haggard (ICN, UCL).

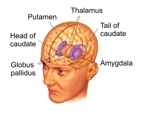

The basal ganglia are a group of subcortical nuclei that are involved in the generation of movements. Parkinson's disease is thought to result from a dysfunction of the basal ganglia. When Parkinsonian patients undergo surgery for the relief of their symptoms via deep brain stimulation, a window of opportunity exists to record from the targeted subcortical structures. I have collaborated with both Peter Brown at the Institute of Neurology and Andrea Kühn at the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, helping to design and program tasks used with these patients to investigate the functions of the basal ganglia.

My earliest research projects investigated the human movement and balance systems. In one study I investigated a rare neurological condition called primary orthostatic tremor. Patients with this condition are unable to stand still for more than a few moments before beginning to shake with a distinctive high frequency tremor. We used a force platform to offer a new way to diagnose sufferers. This work was carried out with Adolfo Bronstein, now at Imperial College. More recently, I've provided psychophysics expertise to assist projects investigating post-stroke foot sensation, led by Jon Marsden at Plymouth.

I also have broader interests in a number of areas of cognitive science (and indeed science more generally, now that my wonderful wife has drawn me into her strange Public Health world). For example, I have been involved with projects looking at conflicts of interest in medical decision making, how calorie labelling affects drink choice, how packaging on cigarette boxes directs eye movements, whether tactile events can yield auditory experiences, how the coordination of the fingers during complex tasks is made tractable, and what role the pre-frontal and parietal cortices play in generating shifts of visual attention and preparing motor acts.

Research Methods

I have conducted studies with both healthy participants and neurological patients, and been an author on publications using a variety of neuroscientific methods, including behavioural and psychophysical techniques, oculography, electromyography (EMG), electroencephalography (EEG), intracranial recordings of local field potentials (LFPs), mathematical modelling, and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). At City St. Georges, I am responsible for the TMS lab.